thomasbroadley.com

Subtracting from the blob

I recently read a blog post called “What Shape are You?”. It’s helped me understand my manager’s perspective on feedback and growth, and given me a new perspective on how to progress in my career. It has some good ideas that I didn’t fully understand at first, so I’m trying to clarify them here.

The article’s main premise is that creative work is subtractive: “you start with a mountain of stuff to get done, and by the time you’re done, someone will have done all of it.” This metaphor is incomplete: Doing a task from the mountain isn’t the only kind of creative work. In fact, the mountain is more like an amorphous blob called “things that we could do”. It doesn’t only contain stuff that you know has to get done (at least to start with).

You can subtract from the blob in a few ways. The first step is to remove low-impact work from the blob and leave behind a set of high-impact problems. Then, you subtract from a particular problem to leave behind a clear solution. You erase more work from the solution to break it up into a set of necessary and sufficient tasks. Finally, you subtract each task by completing it. At the end of a project, you’ve subtracted all the work away, either by doing it or by deciding not to.

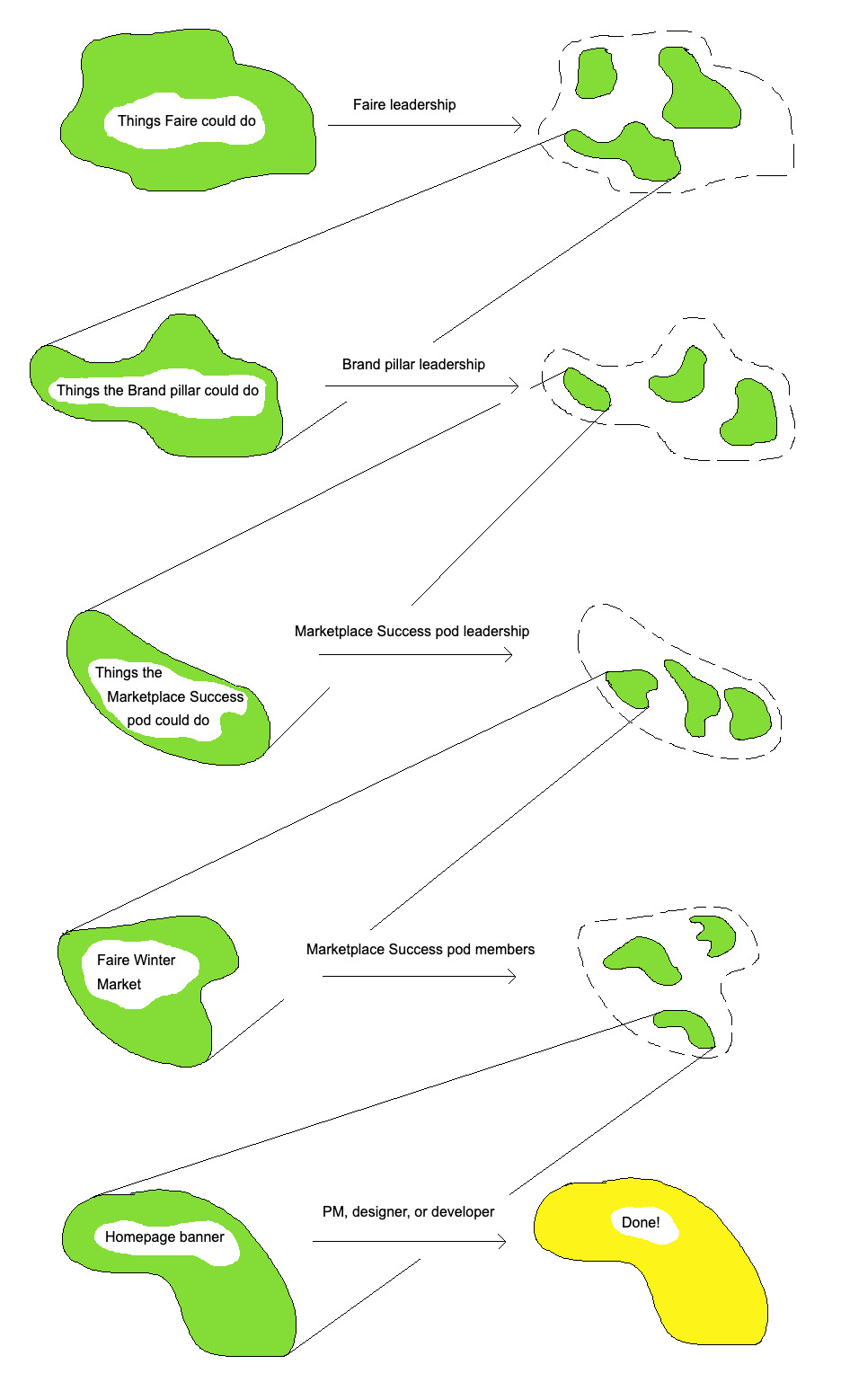

Let’s take this up a level or three. I work at a company called Faire. Our product and engineering team is organized into several pillars, each of which contains several cross-functional pods of five to ten people. For example, I’m a member of the Marketplace Success pod, which is part of the Brand pillar. My impression is that the subtraction process follows this structure:

(I had a lot of fun drawing these blobs.)

At each level, a leadership team starts with a blob called “things we could do”. They subtract from that blob, leaving a few smaller blobs. Then the next level of leadership subtracts further from each blob. Eventually we get to the level of individual problems and solutions. My teammates and I work together to break these into atomic tasks for product managers, designers, and developers. Finally, we complete those tasks. And at the end, the company’s subtracted everything away.

This is a bit simplified. Leadership at each level has some input into the process at other levels. But in general I’m not collaborating with the CTO to decompose a solution into tasks. There’s also a lot of inter-team collaboration that doesn’t show up here, but we can model that as two teams subtracting from the same blob. There might be another level between solutions and tasks, depending on the size of the problem. And this doesn’t account for changing requirements and priorities. I think that looks like adding back work that was previously subtracted.

The thesis of the article is that employees succeed or fail based on the shape of the work they subtract from the blob. One failure mode is subtracting a weird, unexpected shape. Senior employees’ responsibilities are too complex for their managers to fully define or even understand. It’s up to the employee to figure out what it makes sense for them to work on. If they choose poorly, important work can go undone for a long time without anyone noticing.

This has a couple of personal implications. I should look for work that I’m not doing, but that I’m uniquely positioned to do or that everyone is expecting me to pick up. I have a strong suspicion such work exists. When I find it, I’ll probably need to give up work I’m currently doing that other people could also do.

This scares me. I expect it means I’ll spend less time coding and more time scoping, planning, and talking to people. I’m much more confident in my ability to do the former. But I know I can succeed at this challenge.