Learning Workman

Recently I’ve been learning how to type using the Workman keyboard layout. I’ve heard many times that QWERTY isn’t very ergonomic. I decided to learn a new keyboard layout to see how it’d affect my typing speed, accuracy, and comfort, and because it seemed like an interesting challenge. I must admit I didn’t do much research into the other alternative layouts. Basically, Workman’s excellent website convinced me to try it.

I’ve been practicing around 15 minutes a day for the past two weeks. I’ve considered practicing more, but honestly I don’t find the process that fun. Plus, I already spend a lot of time typing, using my phone, and playing the piano and bass, so I don’t want to put too much more strain on my hands.

I’m using Keybr to learn Workman. It teaches you to type using many short lessons, 20 or 25 words each by default, composed of a randomly-generated mix of real and fake words. The fake words are either short, English-like sequences of letters or portmanteaus of two real words. You learn one letter at a time, only moving onto the next letter once you’ve mastered the current one.

I started using Keybr to improve my QWERTY typing but found it annoying to use. I think that’s because I have word-level muscle memory for that keyboard layout. The fake words threw me off because they didn't exist in my muscle memory.

Keybr works well for learning a new keyboard layout, though. Because of the fake words, the lessons don’t force you to type any one word too often, but are still full of common sequences of two to four keys containing the letter you’re currently learning. My hypothesis is that word-level muscle memory is built on top of muscle memory for these sequences. While learning a new key, I first gain muscle memory for the sequences enabled by introducing that key. For example, I learned I and N before learning G, so the lessons only included words ending in “ing” once I started learning G. Besides these sequences, I also build muscle memory for words of four letters or fewer that contain the new key. I then develop muscle memory for longer words. I looked for studies on motor learning that agreed or disagreed with this observation but couldn’t find any.

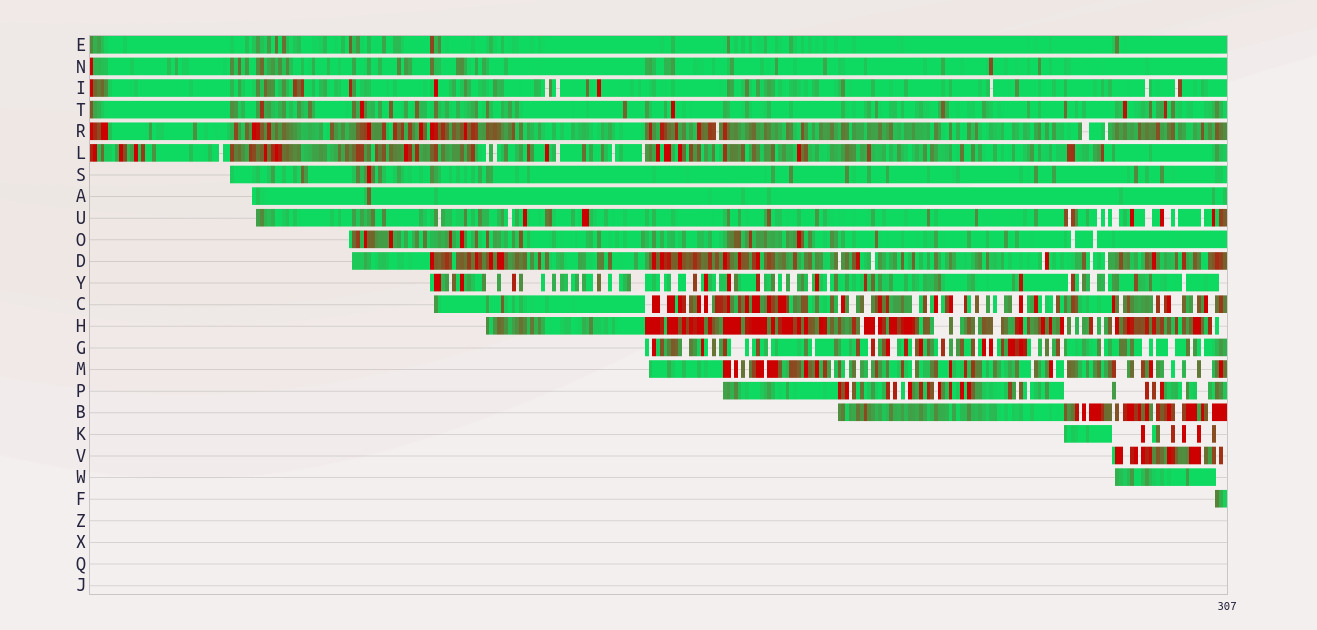

I noticed a couple of factors that made a given key easier or more difficult to learn. It’s easy to analyze them using this graph from my Keybr profile:

The graph’s x-axis is the typing lesson number. You can see I’ve done 307 Workman lessons so far. Red sections represent lessons with lower speed and accuracy for that key, while green indicates higher speed and accuracy.

I found it easy to learn letters that Workman and QWERTY assigned to the same key. Unfortunately, only three of the letter keys I've learned so far are in the same location: A, S, and G. The graph above demonstrates that I quickly learned A and S and haven’t lost that proficiency since. G has been more challenging, perhaps because it doesn’t appear in every lesson.

It was also easier to learn letters that only showed up in short words. For example, in my first lessons for K, the letter appeared almost exclusively in three- or four-letter words like “take” and “ack”. According to the graph, it only took me a few lessons to learn K initially. However, when a later lesson reintroduced it in a longer word, I struggled to remember it.

Finally, learning certain keys completely threw off my muscle memory for the keys I’d already learned. It was like my brain had to break down and restructure my existing muscle memory to take into account the new key.

Take the R key as an example. It was one of the first six keys I learned. It only took me a few lessons to master it. However, my speed and accuracy for R have fallen several times while learning other keys (e.g. A and M). I’ve gone through a similar process of gaining and losing muscle memory with other keys, most dramatically D, H, and B.

It’s frustrating to get less proficient at a key. I wonder whether it would have been faster to learn how to type all the keys at once instead of one at a time. I think I would have abandoned the process because of the steeper learning curve, though.

So far, I’ve learned all the letter keys except for Z, X, Q, and J. After learning those, to help me build word-level muscle memory, I might switch from Keybr to a different typing practice tool that emphasizes typing real words and sentences. I might practice with a tool I developed that uses GPT-2 to generate typing lessons based on a GitHub user’s PR comments. The goal of this project is to let me practice typing text that’s as similar to the text I’m typing on a daily basis as possible.

I’ll also try out Workman at work and in my personal life. I found it

easy to install the layout on Mac OS by following the instructions

here. Ubuntu is more challenging. The GitHub repository I just linked to

contains instructions for four different ways to enable Workman on

Ubuntu. I don’t run xfree86, so that method isn’t an

option. The linux_console and

xorg approaches don’t work on my computer—I think they

might only work on an older version of Ubuntu. The

xmodmap approach enables Workman in Firefox but not in my

terminal. I’ll have to keep investigating.

I’ll write another post once I’ve determined if Workman helps me type faster, more accurately, or with less effort. Even if I go back to QWERTY, learning Workman has already paid dividends: The process has improved my QWERTY typing. I’ve started using the “correct” fingers on more distant keys. For example, I now use my right ring finger to type O and P, instead of my middle finger. I’m not sure how to quantify the impact of this, but I think it’ll slightly reduce the strain of typing.